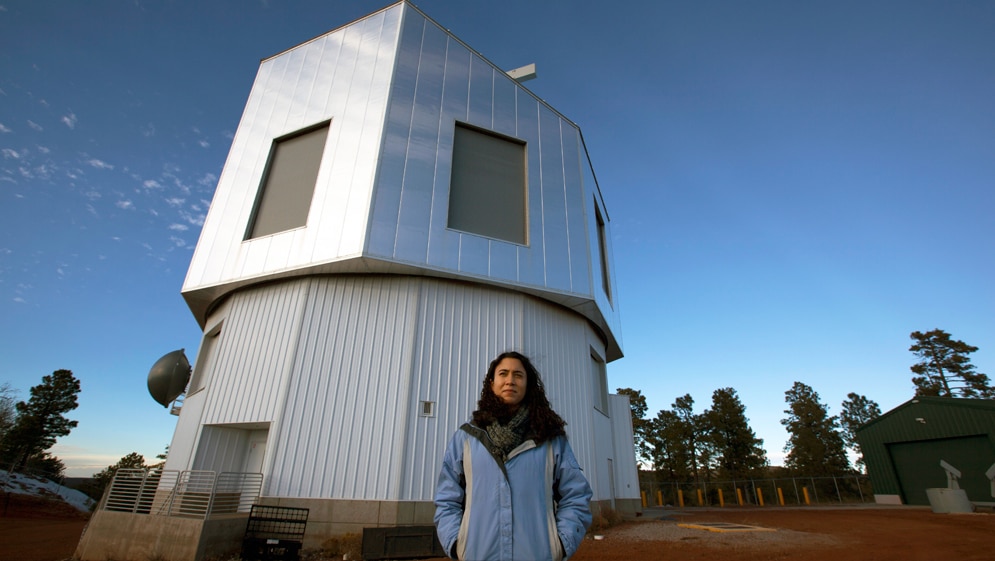

Catherine Espaillat Looks For Baby Planets

Catherine Espaillat’s research centers on an existential question. “How do planets form, in our solar system and beyond?” the Boston University astronomer asks.

She looks to answer this question by studying protoplanetary disks, which are disks of gas and dust orbiting young stars from which planets form. Specifically, Espaillat uses data from multiple telescopes, including the Spitzer Space Telescope, which was active between 2003 and 2020, and the cutting-edge JWST, launched in 2021. The telescopes collect light that the disk emits and split that light into its constituent colors, known as a spectral continuum. Planet formation occurs on the order of a million years, but Espaillat’s team is finding intriguing changes between the light collected a decade ago using Spitzer versus JWST that hints toward changes occurring in the disks. In November 2024, Espaillat was also part of a team that discovered the youngest exoplanet to date, within a protoplanetary disk, using the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite.

In addition to research, Espaillat has taken a special interest in cultivating the next generation of scientific talent. As the daughter of working-class Dominican immigrants, Espaillat has experienced firsthand the distinct challenges of being a young researcher from an underrepresented background. When she began her academic career, she found herself having to learn to navigate the social networks and bureaucracy of academia on the fly.

Outside support was crucial. “I was always lucky that I had people along the way that helped me,” she says. Now, she’s paying it forward by helping students from similar backgrounds. In 2015, Espaillat founded the League of Underrepresented Minoritized Astronomers (LUMA), a peer mentoring group for Black, Latinx, and indigenous women and nonbinary persons. The group has since expanded beyond astronomy to include researchers in those demographics who study physics and earth sciences.

Espaillat spoke to 1400 Degrees about her life, career, and approach to building an academic community.

What was your childhood like?

I was born in Washington Heights in Manhattan, which is a solidly Dominican neighborhood. Then we moved to South Ozone Park in Queens when I was four, which was a mix of mostly Puerto Rican and Caribbean immigrants. During my childhood, my mother was mostly a stay-at-home mom, and in my teenage years, she was a maid at a hotel in Manhattan. My father was a security guard at a local hospital.

My parents instilled in me that education was my number one priority when I was young. My mother was like, “You’re going to study because education is your pathway to a more financially stable life.” Their putting my education first helped get me to where I am today. Even when I told them I wanted to be an astronomer, and they thought I meant astrologer, they always had my back.

Tell me more about your parents’ background.

My mother immigrated in her early 20s for economic reasons. She didn’t go to high school. My father immigrated when he was in his teens. My grandmother, his mother, came with her four teenagers, and she worked as a seamstress in Manhattan. But the kids also all worked because a family of five couldn’t get by on a seamstress’s salary. To get his high school degree, my father did night classes while working full time. He earned an undergraduate degree while working full-time as well.

How did growing up in a working class immigrant neighborhood shape you?

It’s made me really appreciative of the privileges I had. People with my background aren’t typically professors. When you’re from an immigrant and working class background, you’re not used to how the academic system works in this country. You have to find what’s called the hidden curriculum. This is stuff that isn’t officially taught, like how to apply for fellowships. People with family and friends who have gone through academia just kind of absorb this information from their social networks. Now that I’ve grasped a lot of this hidden curriculum, I’m trying to help others with it.

How did you learn the hidden curriculum?

Many people supported me in my studies. As a kid, teachers were always trying to find opportunities that weren’t typically available to enrich my studies. I got a full scholarship to go to a local Catholic high school, but that school didn’t offer many AP classes, so my teachers got me a tutor so I could take the AP calculus exam.

I had amazing undergrad advisors at Columbia, which is where I figured out I wanted to be an astronomer. Joe Patterson helped me get a first-author paper, and David Helfand helped me apply to grad schools. Then when I got to grad school in Michigan, I started asking questions of people in the positions I wanted. Grad students with fellowships shared application drafts with me when I asked. I e-mailed some senior astronomers of color I’d met at a conference to ask if they could share their successful NSF applications. They all agreed to help me.

My Ph.D. thesis adviser was Nuria Calvet, one of few Latina full professors in the field. She’s from Venezuela. She always encouraged me to follow my interests. When I wanted to do observations, but she wasn’t an observer, she told me to go for it. She could have insisted that I focus on research all the time, but she encouraged me to work as a peer mentor in an NSF program. The support from all these people played a big part in why I am here today.

Let’s talk about your research. How do you study how planets form?

I study the protoplanetary disks around young stars around 10 million years old, known as T Tauri stars, to look for evidence of planets. A protoplanetary disk looks like a pancake with the star in the center, but the disk flares out on the edges.

I look for gaps within these disks. That could be a signature of a planet forming in the disk and clearing up the material as it orbits around the star. I also measure the properties of the dust and gas in the disk from which planets form. I’m interested in measuring the sizes and distribution of the dust grains throughout the disk and how their chemical composition changes over time. I then work with theorists who use that information in their models to explain planet formation.

What’s the best-known protoplanetary disk?

TW Hydrae. It’s the closest one to us, at about 40 parsecs, so we have the most data, the most papers, the most everything on it. It’s a transitional disk, which is my favorite type of protoplanetary disk. Transitional disks have holes in them so they’re promising places to look for planets.

Have researchers found any planets in these disks?

Astronomers have robust detections of only two planets in transitional disks so far. In November 2024, I was a part of the team who discovered one of these, TIDYE-1b, which is the youngest exoplanet detected to date. It’s a Jupiter-sized planet that is 3 million years old. It’s about 430 light years away and orbits around its star, IRAS 04125+2902, once every 8.8 days.

In addition to your research, you also run a program called LUMA. Can you tell me about that?

It’s a virtual peer mentoring program for black, Latinx, and indigenous women and nonbinary persons in physics, astronomy and earth sciences. My interest in peer mentoring began in grad school, when I worked for an existing program. When I became a professor, I realized I could create my own. I e-mailed a few dozen people that I knew in astronomy and invited them to join. Most of them did, and they invited more people, and now we have around 100 members, mostly grad students. I’m the director of LUMA, but there’s a paid coordinator and assistant position that I purposely reserved for grad students. They contribute fresh ideas, and they’re more in touch with grad student needs, and this allows me to train the next generation.

We communicate on Slack, and we have workshops about once or twice a semester. We also have a virtual co-working space that we call writing circles. It’s intended to be a safe space for people to talk to others with similar backgrounds without needing to meet in person.

Say a student is interested in forming a group but feels intimidated. What advice would you give them?

Try to join something that exists to first learn how groups work. I got my experience through the NSF AGEP program, which paid me to be a peer mentor. I would organize monthly get-togethers with a few dozen grad students. Then as a postdoc at Harvard, I was the coordinator of WiSTEM, their peer mentoring program for women in science.

But remember that your number one priority is to get a PhD. When you’re more senior, you can create your own thing. Also, it can be a lot to carry on your own. Do it as a team because there is strength in numbers. I consider LUMA to be run by three people: me, the coordinator, and the assistant.

A theme throughout your career seems to be a motivation to create community. Does putting yourself out there come naturally to you?

I’m naturally an introvert. I went into astronomy thinking I would just be looking at stars in a room by myself. To lead this program pushes outside of my comfort zone, but it’s very fulfilling.

What do you like to do outside of astronomy?

I have a beautiful toddler. Most of my free time is just hanging out with her playing, baking, going to the zoo. That’s where I spend my free time nowadays. It’s such a joy to see the world through a child’s eyes.

Sophia Chen is a science writer who covers physics, space, and anything involving numbers. Find more of her work at sophurky.com.

Want to recommend a physicist for us to profile? Write to info@1400degrees.org. All interviews are edited for brevity and clarity.