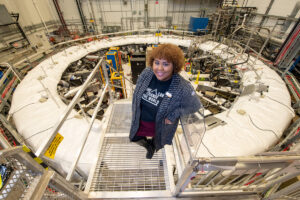

How Authenticity Shapes Jessica Esquivel’s Science

The physics community is on the brink of change, Jessica Esquivel hopes.

First, in terms of the science: The Fermilab physicist is a member of the Muon g-2 experiment, which recently announced a potentially groundbreaking new measurement of the muon’s magnetic moment, a property that dictates how much the fundamental particle wobbles in a magnetic field. The particle wobbles more than theories predicted, suggesting the existence of new particles outside of the Standard Model. At 4.2 sigma, their measurement is tantalizingly close to the 5 sigma statistical significance required to announce a discovery.

“It’s a once-in-a-career moment, to be part of an experiment this close to new physics,” says Esquivel. “It’s a really, really exciting time.”

Then, in terms of the culture: Esquivel, a Black, Mexican, and lesbian physicist, has worked for years to make her professional environment more inclusive to underrepresented groups. Last year, she co-founded #BlackInPhysics, a grassroots movement to build community for Black physicists. She is also part of ChangeNow, a group of Black physicists at Fermilab pushing for equality and justice for Black people at Fermilab.

The work has felt especially urgent after the murder of George Floyd in 2020, says Esquivel. “I need to do this work to move from surviving, to actually thriving,” she says. “It’s making it possible for me to live in my passion for studying physics.” Esquivel spoke to 1400 Degrees about her journey as a physicist so far.

You’re from Texas. What was it like growing up there?

I lived in McAllen, a border town in a region we call the RGV, or Rio Grande Valley. It’s a predominantly Hispanic area. I saw my culture reflected around me every day. I have fond memories of my hometown, but as I’ve gotten older, I realized that being an Afro-Latinx added complexity to living there. I had different experiences than my sister or my mom, who aren’t Black. When I was in retail stores, the employees would follow me everywhere. I felt like I belonged, but people still asked me “What are you?”, and were surprised that I knew Spanish.

How did you decide to study physics?

I made the decision in a collaborative effort with my mom, which happens in a lot of Hispanic families. Financial stability was one of the biggest factors. My mom started working at 16 when she graduated high school. Both her parents died when she was around that age, and she needed a job. She got an associate’s degree and never had the opportunity to “find” herself in college. As I grew up, we moved into the middle class, but when I was young, we were strapped for cash.

We originally decided that I would be an engineer. Our neighbor was an engineer, so we were aware of it as a financially stable career that used math and science, which I loved. Physics was a required course, and I remember quantum mechanics just blew my mind. But my mom and I didn’t know any physicists or what type of money they made. In her words, “I’m not paying for you to be a perpetual student.” So we landed on me majoring in both electrical engineering and applied physics. Later, I learned about graduate assistantships, which would allow me to pursue physics without giving up financial stability.

You apply machine learning to particle physics in your current research. How did you get into machine learning?

I spent a year after college as a contractor for the Air Force in software development, where I learned about computational tools for image processing. I drew on this experience when I went to grad school. For my research, I had to sort thousands of detector images and identify the particles. I looked into machine learning to make the classification easier.

I was one of the first to implement machine learning in a particle physics detector, which meant I had to convince my adviser that this was the right way to go. Many senior physicists were skeptical because they saw machine learning as this black box that we didn’t thoroughly understand. Honestly, I get it. A neural network can identify an image as a human face, but it doesn’t tell us the uncertainty on that prediction. For machine learning to be useful in the hunt for new physics, we need to understand its uncertainties like we do with our other measurements. I’m studying its uncertainties right now.

You’ve been open about being a gay physicist. Could you share your coming out story?

My coming out in physics was with my adviser, Dr. Cardenas, during my junior year of college. We were really close. I went to his office, and I said, “I gotta talk to you about something. I’m dating someone, and she’s a girl. I think I’m a lesbian.” He looked at me and said, “Who cares?” It wasn’t a big deal. Because he was okay with it, it was easier for me to come out to everybody else. The rest of the physics department followed his lead.

Being out has made my professional life easier. I wasn’t out during my gap year with the Air Force, and I was militant about putting a 100-foot wall between my professional and personal life. But my adviser would ask me questions about my weekend plans, and whether I was dating. When we spoke, I kept track of the pronouns, switching “she” to “he,” and it was exhausting. I could have used that energy in my work instead. That experience pushed me to be out in graduate school.

But of my identities, I’ve found that being Black overshadows everything. What people can see takes center stage.

How has being Black affected your professional life?

It depends on my location and the people I’m surrounded by. Texas has this racist reputation, but I felt a sense of community growing up there. In contrast, when I moved to New York for graduate school, I was bombarded with microaggressions and actual racist aggressions regularly. My Blackness followed me everywhere I went. White women would tap their feet at the store expecting me to bag their groceries when I was just waiting in line. I had to learn how to move through the world via trial and error.

One of my survival tactics in grad school was getting a part-time gig at Lane Bryant, the clothing store. I kept it secret because you’re not supposed to do anything but physics in graduate school, but the money wasn’t enough. I also missed being around women. The job was so much fun. I loved playing with fashion and sharing my physics work with my co-workers, who thought it was so cool. But some aspects were negative—customers sometimes treated me like my only worth to society was to sell them clothes.

You’ve shared these difficult experiences publicly in journalistic outlets, on social media, and more. When did you find your voice?

I started talking more about these issues in grad school.

One pivotal moment was a meeting I had with the head of a research award I received. She wanted to make sure that I felt like I had a path to getting my PhD. I was struggling in school at the time and felt ashamed to meet. In our meeting, she told me some shocking stats on black women with PhDs in physics. Dr. Chanda Prescod-Weinstein had just made the news as the 63rd Black woman to graduate with a physics PhD. My success wasn’t just about me anymore. I also learned that I could teach my adviser about my experience so that he could be a better mentor.

But I also needed to recalibrate what success looked like for me. One time when I was working on a difficult homework set, I called my mom at two o’clock in the morning ready to give up. I told her that I felt like was failing women; I was failing black people; I was failing the LGBTQ and the Hispanic communities. She said, “Who made you queen of all these communities?” She was right.

You felt the need to represent the community, but it was also too much pressure for one person. How do you weigh those two conflicting ideas?

I’ve realized the power of being unapologetically myself. I always give the caveat that I’m telling my own story and not anyone else’s. It’s taken away the pressure I used to feel to be this perfect minority.

Once when I was at a panel at Fermilab, I talked about being gay, Black, Mexican, and a woman. A young girl and her mom approached me afterwards, and they were white. They wanted to talk to me about how inclusive physics was for LGBTQ physicists. It’s funny because being a lesbian is the one identity that I can hide. But this girl connected with me because I was open about it.

Sophia Chen is a science writer who covers physics, space, and anything involving numbers. Find more of her work at sophurky.com.

Want to recommend a physicist for us to profile? Write to info@1400degrees.org. All interviews are edited for brevity and clarity